HIV and AIDS: An Origin Story

HIV and AIDS: An Origin Story

When HIV first began infecting humans in the 1970s, scientists were unaware of its existence. Now, more than 35 million people across the globe live with HIV/AIDS. The medical community, politicians and support organizations have made incredible progress in the fight against this formerly unknown and heavily stigmatized virus. Infection rates have fallen or stabilized in many countries across the world, but we have a long way to go.

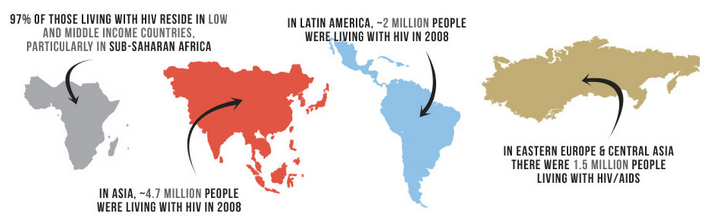

Image via aids.gov. The WHO estimates that 97 percent of the world’s HIV positive population lives in low income nations where anti-viral treatments are scarce or unavailable.

1980s

Beginning in the early 1980s, new and unusual diagnostic patterns began to emerge in different parts of the world. A benign, fairly harmless cancer called Kaposi’s Sarcoma, common among the elderly, started appearing as a virulent strain in younger patients. Simultaneously, a rare, aggressive form of pneumonia began to crop up with alarming frequency in another group of patients. This pneumonia sometimes evolved into a chronic condition, which was something specialists had never seen.

By 1981, scientists had begun to connect the dots between these new diagnoses, plus a number of other opportunistic infections. By the end of the year, the first case of HIV’s full-blown disease state, Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), was documented.

Featured Online Programs

At this point, there was no direct line connecting these early infectious diseases to AIDS. It took researchers several years to fully establish the connection. The initial concern of the medical community was one of contagion, as these mystery viruses apparently spread rapidly among affected populations and began with few symptoms. It was noted early on that young gay men were most likely to receive an HIV diagnosis; a secondary population of needle-using drug abusers was quickly identified as an at-risk patient group. It would be the middle of the following year before it was suggested that HIV was either sexually transmitted or blood-borne on dirty needles.

Identifying the New Syndrome

The early months and years of HIV and AIDS research were marked by rapid change. Scientists not only grappled with a new killer illness that was poorly understood, but the virus itself exhibited new characteristics almost as fast as researchers could identify them. Hemophiliacs, who routinely receive blood transfusions, were also identified as an at-risk patient group. An AIDS outbreak in Haiti further added to the confusion. New cases of heterosexual transmission reinforced early theories that HIV was purely sexually transmitted; however, this theory had to be discarded as mother-child in utero transmission was documented.

There was considerable disagreement among the medical community about how to refer to this new syndrome. Given the sociological parameters of known HIV patients in 1982, early scientists labeled the group of mystery illnesses as a gay-related immune deficiency, gay cancer or community-acquired immune dysfunction. Ultimately, as groups of at-risk patients broadened, researchers dispensed with population-based terminology. By this time there were nearly 500 documented cases in 23 states, all of which had appeared within a year’s time. Other countries across the globe experienced similar outbreaks, and the CDC and WHO began to glimpse the true scope of this scourge.

Particularly in its earlier years, HIV was only understood to be viral, deadly, and highly contagious via unknown means. These variables led to considerable panic on the part of professionals and laypeople alike. Fear fueled prejudice of populations perceived to be at the highest risk for HIV infection. Drug users and homosexuals bore the brunt of the discrimination.

In one national broadcast, televangelist Jerry Falwell echoed the sentiments of some conservative Americans by declaring God had sent AIDS as retribution for the sins of drug using and gay communities. Individuals far outside of at-risk populations overreacted to potential exposure to HIV; mass hysteria resulted in reactions like hemophiliac student Ryan White’s expulsion from middle school and a number other forms of unwarranted discrimination.

Public Policy Responds

As scientists closed in on the source of this illness, public policymakers in America reacted to the epidemic. Bathhouses and clubs catering to gay clientele were closed down, and law enforcement personnel were issued gloves and masks to protect them against potential exposure. The first needle exchange programs were instituted; the FDA began to consider whether the nation’s supply of banked blood was safe. The concept of “safe sex,” now considered standard behavior, was first introduced to the global populace.

In late 1983, the global presence of the mysterious virus motivated European authorities and the WHO to classify the growing number of diagnoses as an epidemic. In addition to the outbreak in the U.S., patients with similar symptoms were documented in 15 European countries, 7 Latin American countries, Canada, Zaire, Haiti, Australia and Japan. Of particular concern was an outbreak in central Africa among heterosexual patients. In the U.S., the mortality rate approached 100%. The first annual International AIDS meetings were held in 1985.

At the end of 1986 and the beginning of 1987, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) administered a clinical trial of Azidothymidine (AZT), the first drug to prove effective against the rapidly replicating HIV virus. Originally a chemotherapy drug, AZT worked so well during its trial that the FDA halted the trial on the grounds that it would be unethical to deprive those patients who received a placebo of the actual drug.

1990s

By 1993, over 2.5 million cases of HIV/AIDS had been confirmed worldwide. By 1995, AIDS was the leading cause of death for Americans age 25 to 44. Elsewhere, new cases of AIDS were stacking up in Russia, Ukraine, and other parts of Eastern Europe. Vietnam, Cambodia and China also reported steady increases in cases. The UN estimated that in 1996 alone, 3 million new infections were recorded in patients under age 25.

Countless deaths in the U.S. entertainment industry, the arts and among professional athletes deeply affected these communities ― and the rate of death would not slow significantly until 1997. During this time the U.S. government enacted legislation that directly affected HIV-positive people. These individuals were legally prohibited from working in healthcare, donating blood, entering the country on a travel visa, or emigrating.

Research and Policy Breakthroughs

Meanwhile, research scientists were gaining ground. The course of infection was better understood, and the clinical definition of HIV and AIDS was refined. Other drugs went into trial, with mixed success. A drug known as ACTG 076 showed particular promise in mother-to-infant transmissions, and a drug called Saquinavir was approved by the FDA in record time. Viramune followed these, further expanding treatment options for HIV-positive patients. Combination therapy approaches developed in 1996 were especially effective, and by 1997 a global standard of care had been adopted.

Public policy during this period took a brave step socially. The condom, rarely ever spoken of in polite company and used even less, became less taboo and more widely used than ever before. Condom sales took off in developed countries, quadrupling in some areas. This was due to the efforts of the CDC; similar campaigns in the UK and Europe sought to slow the spread of AIDS by promoting safe sex. President Clinton’s administration aggressively advocated for HIV/AIDS education and funneled more federal resources toward AIDS research. Internationally, the WHO AIDS program was replaced by the UNAIDS Global Programme that is still in existence today.

HIV/AIDS in Africa

In most of Africa, public opinion was backed by the leadership of African politicians who refused to acknowledge the existence of sex between men, let alone a health crisis that affected a nation’s homosexual population. In many countries, homosexuality was and still is a criminal act; it was not uncommon for early AIDS activists to end up in jail. In countries where the gay social network operated underground, reaching the population with lifesaving education and antiretrovirals was near impossible.

Furthermore, in African nations, public policy was focused on treatment options, versus the needle exchange programs and safe sex awareness campaigns found in other parts of the world. Unfortunately, a lack of trained healthcare professionals made it difficult to administer the medications that might have slowed the rate of HIV infection in these countries.

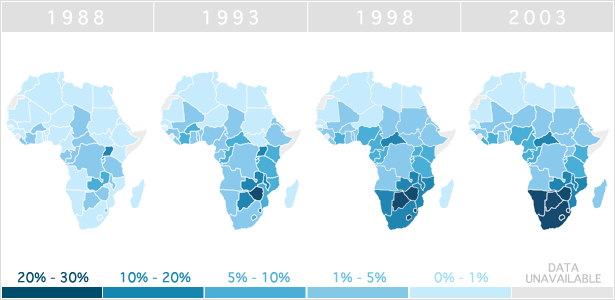

By 2003, AIDS would overtake swaths of the African continent; nearly 40 percent of Botswana’s adult population was infected, with similar percentages in Swaziland. The outlook was especially grim for the children of HIV-positive adults. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) estimated that by 2010, 40 million children in developing African nations would have lost one or both parents to AIDS.

Image via Avert.org. Insufficient responses to early outbreaks of HIV/AIDS in African countries caused infection rates to skyrocket in the 1990s. Even today, over 97 percent of the world’s HIV-infected population lives in Africa.

While HIV and AIDS had been noted in sexually active heterosexual groups in central African countries from the earliest days of the epidemic, popular opinion that HIV was largely contained to gay communities endured well into the 2000s. This line of thinking had stalled education and prevention efforts in the U.S. and abroad. But as HIV gained a footing in new population groups, global leaders made historic if not overdue efforts to stop its spread in developing nations.

Where We Are Now: 2000-Today

Since 2000, additional factors have begun contribute to the the global spread of HIV. Heroin addiction in Asia has been on the rise, which brought with it dirty needles and the risk of new infections. India suffered with over 2 million diagnoses alone, in spite of the government’s refusal to admit the epidemic had adversely affected the nation.

The WHO released its comprehensive report examining HIV and AIDS in all of its 25-year history in 2010. This report had good news for developed nations: by 2008, the U.S. domestic HIV infection rate was considered effectively stable, and has remained so to this day. The report also demonstrated that while insistent public awareness campaigns about safe sex and other methods of transmission had slowed the rate of HIV infection in developed countries, there was much to be done elsewhere.

Global Education and Aid Efforts

Under President Bush, the U.S. committed funds to help African countries, but the funds were mismanaged and the spread of HIV continued unabated. Of the 4.1 million cases in sub-Saharan Africa then, only 1% received the available drugs. This led to the WHO’s declaration of the failure to treat the 6 million AIDS patients living in developing nations as a global public health emergency.

In 2003, the WHO announced its ‘3 by 5 Plan,’ wherein 3 million people living in undeveloped countries would gain access to treatment by 2005. Financial problems plagued the initiative. Ultimately, private philanthropists and the U.S. government funded the delivery of crucial antiretroviral medication to 15 African countries. The 3 by 5 Plan was unsuccessful, but it did drive a renewed push by the WHO to deliver care to sub-Saharan Africans by 2010.

Several countries were unable to properly manage funds given to them. Other governments refused aid packages that came with certain use stipulations that they found offensive or immoral. For example, Brazil took issue with the U.S.’s refusal to condemn the role of sex workers in HIV infection, turning down $40 million in aid.

HIV Denialism Disrupts Aid

What had begun as a crisis within the medical community had taken on decided political overtones by the mid-2000s. Members of the UN and individual governments operated multiple initiatives; sometimes entire continents were targeted, and sometimes local government strove to reduce infection rates on home turf.

Unsurprisingly, political disagreements affected the flow of cash, often stalling or outright preventing certain populations from receiving treatment or information about HIV. Several governments bowed to stigma and failed to address rampant HIV infection at all. In South Africa, President Thabo Mbeki continued to ignore the advice of scientific authorities to increase access and availability to antiretrovirals in his country. Mbeki’s Presidential AIDS Panel claimed the link between HIV and AIDS was not well enough established and that the toxicity and efficacy of HIV treatments needed more study, catastrophically blocking the use of common treatments like AZT throughout South Africa.

By the time Mbeki was recalled from the presidency in 2008 and one year before the FDA approved its 100th HIV/AIDs drug, an estimated 16.9% of South Africans aged 15-49 were HIV positive.

One notable exception to denialism among African national governments was Uganda. Aggressive public awareness efforts educated Ugandans about safe sex and safer drug use, and as a result, the rate of HIV infections was halved over a ten-year period. This success allowed African nations to overcome the societal taboos that prevented frank discussions about safe sex. Globally, public awareness was at its highest since the AIDS crisis had begun, but this awareness had yet to reach sub-Saharan African countries.